|

AMP gauges at the dash are

troublesome.

They should be by-passed, and then

install a VOLT gauge.

by Mark Hamilton

THE

PROBLEM

The antiquated AMP gauge system has reduced more

Dodge owners to pedestrian status than any other kind!

And (wire) “terminal illness” at firewall

connectors has also been a major problem.

(Chrysler Corp. stayed with the old AMP gauge

system long after other automakers switched to VOLT gauges,

and Dodge trucks used the AMP gauge more recently than others,

so we have used a Dodge truck as a model for this

project.)

Dodge is not the only make with concerns about

AMP gauge systems, early FORD Broncos, International SCOUT,

and many old cars and trucks used the AMP gauge system

too. But when the

electrical system will be up-graded with more powerful

alternators and more accessories, the AMP gauge should be

removed, and the “main power system” should be

modified.

With normal but frequent use, most of these Dodge

trucks will have electrical wiring problems. The first to fail were

often the trucks equipped with factory air conditioning. The air conditioning

system adds a significant electrical load. And the “air” gets

used in hot summer weather when heat will increase resistance

at connections.

The additional current flow when using the air

conditioning and increased resistance with heat will break

down the weak areas more quickly. With sufficient use,

the non-air equipped trucks will also have electrical problems

stemming from the same cause.

Typical Dodge electrical problems result from a

very antiquated power distribution system. The main source of

power for the Dodge electrical system is based upon an old

design AMP gauge at the dash and related wiring system. It’s a system that

worked okay with a very small electrical system on Model A

Fords way back in the late 1920’s. But the old

AMP-gauge-at-the-dash system is not reliable with increased

current loads of the more modern electrical system.

Compounding the situation, the wiring system for

the AMP gauge actually became weaker than it was over fifty

years earlier.

Assembly line labor was not so expensive in early years

of the car.

Affordable labor could consistently connect wires with

“ring terminals” at screws or studs with nuts–resulting with

reliable (low resistance) connections. With increased labor

cost mandating fast moving assembly lines, and many more

wiring circuits to install, “click together” connections have

been widely used since back in the 1950’s. And by the 1960’s,

even the AMP gauge (heavy current load circuit) was routed

through a “click together” connection. The least reliable of

“click together” connections for a heavy current load circuit

is the male/female flat blade terminal design. And it happens that

Dodge was built with this terminal design, even at the main

power delivery circuit.

In summary, the AMP gauge and related wiring

found in Dodge trucks of the sixties and seventies period was

built with a recipe for failure. A 70amp alternator

supporting powerful electrical accessories was typical

equipment by 1979, and the load was too much for the method of

wiring construction used. Naturally, it’s a

system that often reduced Dodge owners to pedestrian

status.

This feature clearly explains the shortcomings of using

the old, traditional, AMP gauge at the dash. And largely because of

the circuit design shortcomings, the best choice of gauge to

monitor the electrical system is a “VOLT” rather than AMP

gauge. A good

explanation of the AMP vs. VOLT gauge may be found at

http://www.autometer.com/

in the Tech Tips / FAQ section of the web sight.

THE HISTORY

In some

ways, the Chrysler Corporation was pretty far advanced where

electrical systems were concerned. (Chrysler gave us the

Dodge, Plymouth and Chrysler line, and nowadays they all may

be referred to as MOPAR.) Back in the early

‘60’s, MOPAR was the first to give us alternators rather than

the older technology generators–Indeed the improvement was

great. GM

followed, and then Ford finally installed alternators as

“standard equipment” on ’65 models.

1964

year model Chrysler products showed up with “Fusible Link

wires” for reliable short-circuit protection of the main power

circuit from the battery to the electrical system. Chevy didn’t use

Fusible Link wires until ’66 models.

And

Ford didn’t use Fusible Links until some years after GM.

Chrysler/Dodge/Plymouth

introduced a very good electronic ignition system with 1971

models. Ford

introduced a somewhat less reliable electronic ignition with

only some of their ’74 models. And GM gave us a very

good electronic ignition with ’75 models.

In

spite of being the first to give us “break through” technology

with components, it seems that the “DODGE BOYS” were reluctant

to depart from a very antiquated wiring system. The old, traditional,

“full current load type” AMP-GAUGE-AT-THE-DASH and related

wiring system was still in use with ’79 Dodge trucks. The AMP gauge circuit

wiring had to deliver electrical current used by the entire

electrical system, plus handle current to recharge the

battery. The

problem was that current load and the alternator output rating

was a large amount by the end of the ‘70’s. Alternators with about

a seventy amp available output were standard with

air-conditioned models.

And a weak terminal design was used where the AMP gauge

wiring passed through the firewall. The large demand for

electrical current often resulted with failures in the lengthy

AMP gauge circuit, even in vehicles that were relatively

new.

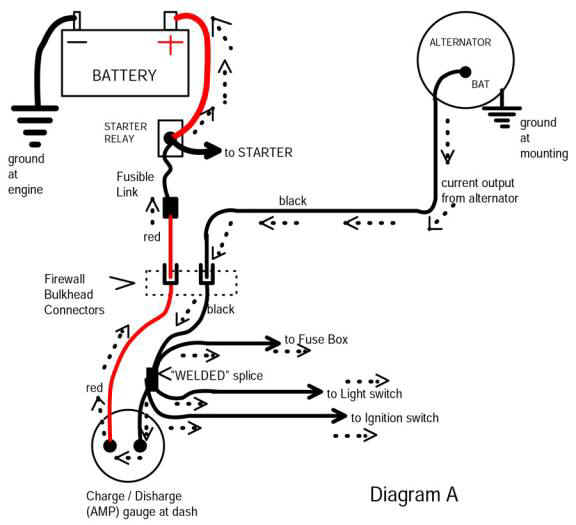

The original AMP gauge system

served as the main power distribution system. This circuit is the

power source for the entire electrical system. (see diagram

A)

Amp

gauges at the dash were standard equipment with Model A Fords,

back in the late 1920’s.

And the fifteen amp capacity gauge at the dash worked

fine with minimal electrical systems of that period. Current output from

the small Model A generators was not even sufficient to

support sealed beam headlights. (The old Model A was

equipped with a small light bulb backed up by a large

reflector in the headlight assembly.) The Model A only had

one tail/brake light at the rear, a simple ignition system and

a small battery about completed the electrical system. Such a small amount of

electrical current flow through good connections at the AMP

gauge wiring was no problem with the Model A Ford. And with current

output limited by a cutout relay on the generator, the AMP

gauge could handle the small battery charge rate. But as electrical

systems became more powerful, Ford discontinued the old AMP

gauge system long before the ‘70’s.

GM

also up-graded their system long before the Dodge Boys. When GM introduced the

alternator with ’63 models, it was controlled by a more

complicated but more efficient voltage regulator system. And the new GM system

could support a warning light at the dash. The warning light was

often standard equipment and the gauge was an option. GM

vehicles built with the gauge option also had a more modern

design of AMP gauge at the dash. The newer AMP gauge

was a remote shunt type design–a length of the battery

charging wire in the under-hood harness served as the

shunt. The dash

gauge and related wiring no longer handled heavy current

load. Same with

Ford in ’65 and newer model cars–the Ford system could work

with a warning light at the dash, and cars that came dash

gauges had a remote shunt type amp gauge.

The

Dodge alternator/voltage regulator system

had no provision to operate a warning light. And Dodge (trucks)

stuck with the old antiquated “full load type” AMP gauge

design, at least into the late 1980 models. As is typical of Dodge

trucks that were used a lot, the AMP gauge in this ’76 Dodge

was burned out.

The plastic mounting area behind the dash is completely

melted, and the lens and plastic trim is shriveled too. (This gauge is

included in Diagram A.)

Amperage

is a measure of current flow, and all of the current used to

recharge the battery was routed through this gauge–which

caused the gauge to display the battery charge rate. Both the alternator

and the battery were mounted up front, under the hood. And the AMP gauge was

at the dash. It

was an arrangement resulting with a very long wire circuit

charging the battery.

Large amounts of current flow through the AMP gauge

will generate some heat too. The plastic cover at

this gauge was only distorted by heat–but some Dodges have

sizable holes burned in the dash where the AMP gauge used to

be. Apparently,

the shunt in the gauge has a sufficient amount of resistance

to generate a damaging amount of heat with battery charging

current flow.

A

previous owner had replaced the terminals at the back of the

AMP gauge, and then did a weak by-pass of the gauge by taping

the two wire terminals together.

(No doubt an attempt to get the old Dodge up and

running.)

It’s fairly common to find the wires disconnected from

the gauge, and a machine screw and nut clamping the terminals

together, and finished by wrapping the screw and terminals

with tape.

The AMP gauge wiring passed

through the “firewall bulkhead connector,” where standard,

.250 inch wide, male/female flat blade connectors were

used. (This

connection is shown in Diagram A.) These terminals were

reliable with circuits of much less current flow, as with turn

signal, clearance lights, and temp or fuel gauges. But the design was

certainly not up to the job of handling the entire alternator

output. This was

a problem spot in the AMP gauge system that often made Dodge

owners walk.

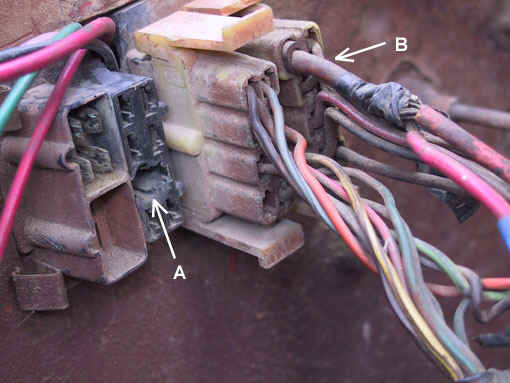

Arrow A in the photo at the

left points out a melted cavity in the plastic connector body,

where a case of “terminal meltdown” occurred. This connection served

as a pass-through for the main wire from the alternator to the

dash area. When

driving, the entire electrical system current load will pass

through this connector.

(Also seen in Diagram A.) Ignition, lighting,

heater fan, accessories, and electrical power in general flows

through the connector. The wire color code is black at this

circuit, and this model was equipped with 10 gauge wire. (Many earlier models

had only a 12 gauge black wire.)

Arrow B points out the red, 10 gauge,

battery charging wire.

After removing

the connector with the red 10 gauge battery charging wire, a

close inspection revealed that this side of the AMP gauge

circuit was also suffering from a case of “terminal

illness.” (See

arrow in photo at the left. This is the terminal

used by the 10 gauge red wire at arrow “B,” above.))

The plastic connector body

surrounding the female flat blade terminal is beginning to

melt away. And

severe oxidation of the terminal itself is evidence that this

terminal has been glowing hot. Notice that the other

terminals in the connector body are still in good

condition. The

rusty appearance of this terminal is typical of wire terminals

that have been hot while handling large amounts of current

flow. (If

moisture had caused the oxidation, all the terminals would

have been corroded.)

We have opened part of the dash wire harness, to show

the factory “welded splice” where wires branch off to the

ignition switch, light switch, and the fuse box.

(This splice is shown in Diagram A.)

The “welded splice” is insulated by a factory

installed, sticky cloth tape.

The

original tape has been removed for this photo to expose the

“welded spice.”

Pressure and heat fused

the copper wire strands together when making the splice. The method seems to be

reliable, as in thirty years of workshop experience the author

has never seen a failure with this splice. When electrical power

loss occurs, this is certainly not the first place to look for

the problem.

Click

here to see Part 2, where we

will by-pass the gauge and repair the wiring

|